Write-up FCSC 2023 : Video Games Awards

2023-04-30 22:00 +0200I - Intro

Video Games Awards or VGA1 consists of a floppy image that can be booted with a virtualization or emulation software.

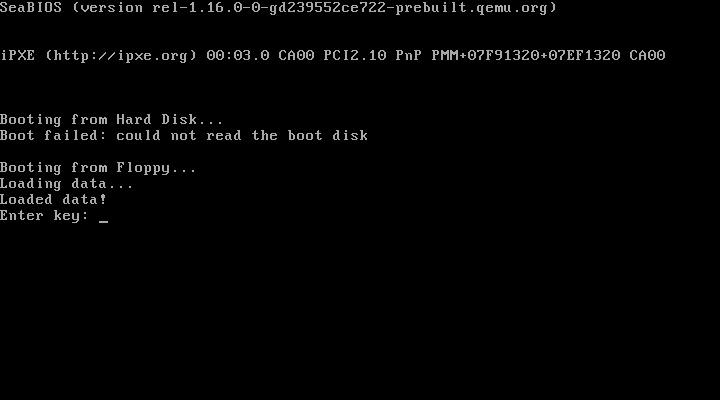

Let’s start with qemu :

We can enter a key and we get a great failure screen :

II - Reversing the boot sector

It is fairly common knowledge that the BIOS of IBM PC compatible computers (i.e. 99.9999% of non UEFI x86 machines) load the first sector of the device they want to boot from. We can extract the first sector of the flopy using dd and import it into Ghidra at address 0000:7c00.

The first thing the boot sector does is relocating it self at 0000:0500, we can then use the Ralf Brown’s Interrupt List to identify the print and load_disk routines, which uses the VIDEO - TELETYPE OUTPUT in int 0x10 and DISK - READ SECTOR(S) INTO MEMORY in int 0x13 respectively.

After priting “Loading data…”, the boot sector will erase the boot sector and load the rest of the program from the floppy at 0000:0700 before jumping to it.

MOV SI,0x5ca

CALLF print ; "Loading data..."

MOV byte ptr [DISK_ID_BACKUP],DL

MOV DH,0x0

MOV CX,0x810 ; Head 0, Cylinder 8, Sector 16

MOV DI,0x1 ; Read 1 sector

MOV BX,0x7c00

CALLF load_disk

JC ERR_Geometry

MOV DH,0x0

MOV CX,0x2 ; Head 0, Cylinder 0, Sector 2

MOV DI,0x3 ; Read 3 sectors

MOV BX,0x700

CALLF load_disk

JC ERR_Generic

MOV SI,0x5da ; "\nLoaded data!\r\n"

CALLF print

CALLF 0000:0700

CALLF 0000:0788

III - Reversing the main program

We now know where the main program is located on the floppy and at what address it’s loaded. We can extract it and import it in Ghidra.

There are two main functions that are called from the bootloader. The first one at 0000:0700 is responsible from reading the input from the user. We can easily identify the use of the int 0x16 which relate to the keyboard

It will read up to 0x40 characters at 0000:7c00 and will even use the (very pleasing to hear) PC buzzer when we hit the limit.

The main part of the program is located in the second function, as this is where the input will be checked. This function uses a lot of IN and OUT instructions, we never see them on userspace programs beaucoup they are not allowed in Ring 32, but they are used to send data through the I/O ports of the processor.

Nowadays the I/O ports are mostly dynamic and assigned by the PCI controller, but back in the days of ISA the configuration (such as I/O ports, DMA channels, MMIO addresses or IRQ numbers) of each devices was hardcoded or settable via jumpers and it was the resposibility of the user the ensure that there weren’t any conflicts. This of course required some setup on the software side to inform the driver of the location of said device, this can’t be done for devices required early at boot, such as the keyboard controller, the disk controller or the video card.

By looking up the OSdev Wiki we find out that most of the used ports are related to the VGA Card, thus the acronym of the challenge.

IV - VGA shenanigans and DOSBox instrumentation

With my limited OSdev experience, I know that most of the time when programmers wanted to use VGA, they were helped by the VGA BIOS and its interrupt : int 0x10. It will do most of the heavy lifting as the VGA controller is a pretty complex beast.

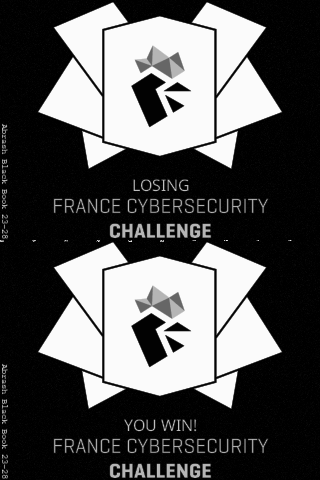

After searching for a while I didn’t find a comprehensive list of I/O ports or registers, they were mostly incomplete or irrelevant. A hint was provided by the failure screen : “Abrash Black Book 23-28”.

The Michael Abrash’s Graphics Programming Black Book is a book about video programming on the PC and a huge source of information about VGA. The sections 23 to 28 are realted to its internals and how to program it without the VGA BIOS. This is pretty long and I was only able to skim through it but it gave me pointers to what to look for.

Indeed we completely lost track of our flag, what does it have to do with VGA ?

In the middle of the main function we can find references to our input :

MOV BX,0xa4b0

MOV ES,BX

MOV BX,0x7c0

MOV DS,BX

XOR SI,SI

MOV DX,0x3c4

MOV BX,0x102

PROCESS_FLAG_2:

MOV CX,0x10

XOR DI,DI

MOV AX,BX

OUT DX,AX

PROCESS_FLAG_1:

MOV AL,byte ptr DS:[SI]

ADD SI,0x4

AND byte ptr ES:[DI]

LEA DI,[DI + 0x8]

LOOP PROCESS_FLAG_1

INC SI

AND SI,0x3

SHL BH,0x1

TEST BH,0x10

JZ PROCESS_FLAG_2

The inner loop seems to be copying part of our input from 07c0:0000 (which is the same as 0000:7c00 thank to real mode segmentation) to a4b0:0000.

I remembered from the VGA OSdev Wiki article that VGA memory start at a000:0000, so the input is being copied deep into video memory. This is pretty surprising, but after my very quick and incomplete readthrough of Michael Abrash’s Graphics Programming Black Book, I remembered a compare mode that can be used to easly check for area of a speicfic color.

Our input is probably impacting the content of the video memory and will let the check go through if we enter the correct one.

However I was still surprised by how far it was written, the video memory should contains something else than the sole image we are seeing.

As I was already looking through DOSBox source code for a reference about the I/O ports and VGA registers, I made a debug build of it and loaded the challenge. That way I was able to attach gdb to it and dump its video memory.

(gdb) print vga.mem

$1 = {

linear = 0x7ffff5704010 "",

linear_orgptr = 0x7ffff5704010 ""

}

(gdb) dump memory vga_memory.data vga.mem.linear (vga.mem.linear + 256*1024)

We immediatly notice the presence of both the winning and loosing image : the program will shift the view when the check is validated.

An other odd thing is some dots on the part the image were our flag is written. We can assume the selected read mode will probably compare them.

I took a close look at the first ones and the last one to compare them with the flag format (FCSC{....}):

| Byte in video memory | (hex) | (bin) | Flag character | (ascii) | (bin) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

0xC8 | 11001000 | F | 01000110 | ||

0x68 | 01101000 | C | 01000011 | ||

0x6A | 01101010 | S | 01010011 | ||

0x68 | 01101000 | C | 01000011 | ||

0x6F | 01101111 | { | 01111011 | ||

0xAF | 10101111 | } | 01111101 |

The first obvious fact is that there are the same numbers of ones on the character and its correspoding byte in the video memory. This is probably related to the way the VGA planes work.

I could’ve tried to look for the correct mapping beetween the bits exposed to the processor and the bits stored in DOSBox memory but with the flag format I had enough information to do the correspondence by hand.

V - Conclusion

The solve script ends up just reading the content of the dump and shuffling the bits arround :

def decode_byte(x):

o = 0

o |= ((x >> 0) & 1) << 3

o |= ((x >> 1) & 1) << 4

o |= ((x >> 2) & 1) << 5

o |= ((x >> 3) & 1) << 6

o |= ((x >> 4) & 1) << 7

o |= ((x >> 5) & 1) << 0

o |= ((x >> 6) & 1) << 1

o |= ((x >> 7) & 1) << 2

return o

out = b""

f = open("vga_dosbox_dump.data", "rb")

f.seek(0x12C00)

for _ in range(16):

out += f.read(4)

f.read(7*4) # We jump over the "gaps"

print(bytes(map(decode_byte, out)))

$ python3 solve.py

b'FCSC{465263d0fd5d89dc6ae2dde6a7fa360c472e6ed0528ba12b87cb7f7ede}'

We can now use the flag as input to check its validity.

Foreshadowing is a narrative device in which a storyteller gives an advance hint of what is to come later in the story. ↩︎

Assuming the IOPL is less than 3. As far as I know it is 0 on most x86 operating systems. ↩︎